Interview with social anthropologist Raoul Galli

What is trade union capital?

What is ”trade union capital” for? Researcher Raoul Galli has studied what is recognized in the trade union world based on Pierre Bourdieu’s theory.

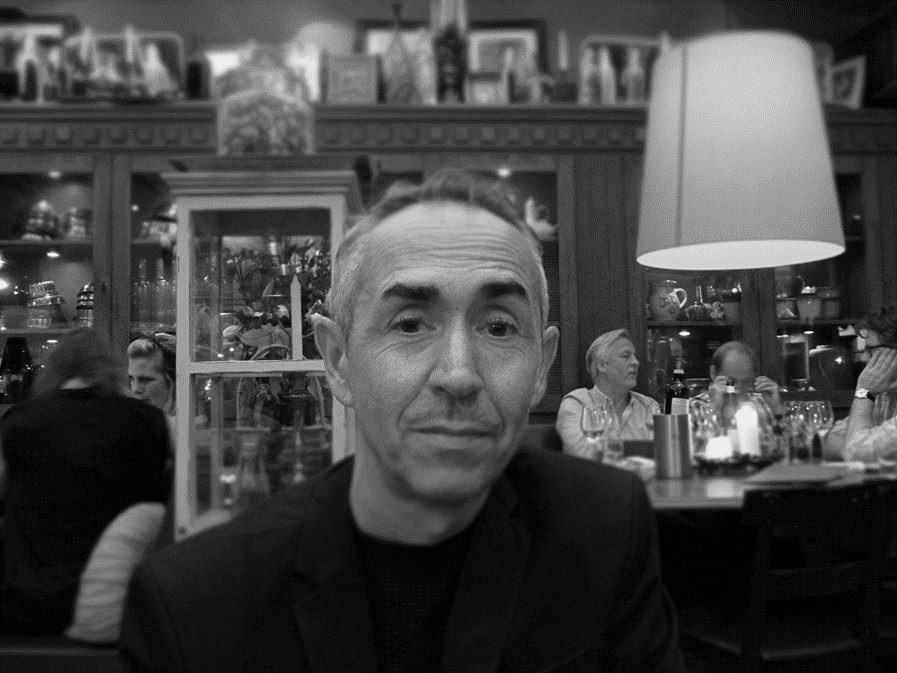

When I speak to Raoul Galli, I am struck by his academic language and measured gestures. On pure intuition, it is possible to imagine that it is a university person’s figure I have in front of me.

That’s pretty guessed! Raoul is a social anthropologist, researcher from Stockholm University. The fact that it is possible to draw conclusions from a person’s way of being and moving also confirms Raoul’s own scientific theory – taken from the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu – that our social experiences are engraved in the body, our so-called ”habitus”.

One day in mid-February I meet him at TAM-Arkiv’s premises. Dealing with the changing meaning of white-collar and academic concepts, it’s all projected against a backdrop of an upcoming anthology – initiated by TAM-Arkiv and in the works.

Raoul has been commissioned to study the current trade union brand strategy through an anthropological micro-study. He has conducted a number of in-depth interviews with brand managers within both Saco and TCO. The background is that he has previously written a thesis on how to gain recognition in Stockholm’s advertising world.

How do you gain recognition in the trade union world? What are his thoughts after he interviewed the trade union representatives? These are the questions I look for answers to during our conversation.

Social background

I’ll start by asking Raoul about his background. I must have thought he was born in Italy, that’s where he originally came from. That was not the case. It was Sweden. His gaze shifts slightly. ”Hm, hm, hm, hm” – that sounds like some kind of laughter. But after a few seconds, he regains his composure and answers:

”Anyway my family is from Italy.”

In Sweden, the family first settled in a tenancy in Botkyrka. Then they made a housing career, moved to a townhouse in Handen, and ten years later settled in a villa in Saltsjöbaden. He remembered that he perceived the new school environment in Saltsjöbaden as difficult:

”Suddenly I could see boys my own age walking in sailor jackets and briefcases at school. In Saltsjöbaden I could not recognize myself in the youth culture that simply prevailed,” he says reminiscingly.

Whereas in Handen young people would be wearing bubble jackets and carrying adidas bags. In Saltsjöbaden, girls and boys often looked like adults even though they were children. For Raoul, it signalled a super tediousness and he longed to return to Handen. Raoul came into contact early on with social differences. When he began studying anthropology, he became hooked on Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of social power, status and hierarchy. According to Bourdieu, achieving social recognition is a universal human driving force.

What hierarchies?

What hierarchies are there in the trade union environment? How have they changed? Raoul firmly notes that despite the fact that calling oneself ”white- collar worker” does not breathe the same weight and status today as it did in the 1920s, for instance, it is still used in trade union contexts. In the trade union world, people talk about ”workers”, ”officials” and ”academics” as if it were set in stone. According to this way of seeing, ”workers” are at the bottom, ”officials” somewhere in the middle, and ”academics” are at the top. Within TCO, one can talk about officials as an ”intermediate layer”. Something that may have made it easier to embrace brand thinking. Raoul has not got the feeling that there is a ”class struggle” directly advocated within the TCO and Saco associations:

”But nevertheless, some kind of class struggle is working in full even as we speak,” Raoul ponders deeply – “white-collar workers do really care about their ‘class identity’; otherwise as we know full well, one could have merged trade unions; the fact that this does not come about shows that differences between groups are perceived in-depth.”

But there is not only hierarchical ”vertical” competition between unions. There are also ”horizontal” differences. For instance, in an interview with a representative of a Saco association, one person said they were ”the left-wing association of Saco.” If there are ”left-wing associations”, there should also be ”right-wing associations”, Raoul thought. He finds it rather intriguing that there are such coordinates in people’s thinking about different covenants.

The fact that the trade unions have changed their strategy and used more brand thinking – this has contributed to an increase in the number of members. The concept of white-collar workers has been patterned out of names of unions, federations and associations, the concept of academics has become increasingly important.

Are there any disadvantages?

But are there any disadvantages to the union’s current brand strategy? Raoul believes that there may not be such a great negative consequence to engage in brand thinking in the trade union world. When everyone else is doing it, why shouldn’t the unions do it, you might think. At the same time, there is a risk that many people will not feel comfortable with it. Today’s trade union advertising – with ”superheroes” and young, good-looking people – may not be what we usually associate with trade union advertising. But that’s the way unions survive in a changed world, he thinks. It’s a way to recruit new members and to gain recognition out there in society. And this is done in today’s situation with advertising and branding rather than by, for instance, going out and agitating for the rights of employees.

But a potential problem with unilaterally investing in image and brand issues, he believes, could manifest itself on the day you want to go on strike. Members may not have thought that they are part of a union struggle. That trade union work can not only go through negotiations, but also by going into conflict.

A trade union capital

Is there a ”trade union capital”? Pierre Bourdieu believes that not only should we count on economic capital, but that there is also a cultural (educational) capital and social capital in the form of a network of contacts. Finally, he expects a ”symbolic” capital something that can be basically anything that gives social recognition within a specific group. Those who are active in a particular field perceive a special quality in another person that is good to have right there. This property gives a reputation, this gives status.

Is there a specific ”symbolic capital” in the trade union world? Raoul has tried to ask the question but has not received an easy answer. There are probably different things that give a reputation in the trade union world depending on your position. If you are a negotiator, you can gain a reputation, but you can also get it as a trade union ombudsman or leader through other qualities. But Raoul believes that it is always interesting to try to bake these different properties into something that you could call a ”trade union capital”. And try to understand what the distribution of this looks like in the trade union world.

Would the trade unionists get anything out of reading Pierre Bourdieu’s sociological writings? Not because they are unionists, Raoul says. But he believes that we would all benefit from reading Bourdieu:

”Trade unionists – as people – would benefit from reading Bourdieu because one might understand oneself better, where you come from and what you bring with you. But also what affects you through the journey.”

Through things like education, different jobs, career or not career, you change. And through these changes, one’s perspective on existence changes at the same time.

Bourdieu was also in favour of trade union organization. He co-founded the Attack Movement and talked about an international for intellectuals. That idea came from the Workers’ International, Raoul says. Bourdieu argued that employees who want to organize should do so in order to put pressure on economic capital. And perhaps not only within the borders, but also outside of them.

We’ll round off the conversation. What does Raoul discover? Behind our chairs there is a bookshelf with some interesting books. He studies in detail some of the volumes. Sociologist Wright Mills’ book The Power Elite arouses his special curiosity. The last thing he does is borrow this early study of the military-industrial complex in the United States.

By Leif Jacobsson

Master of Philosophy in social anthropology and co-worker at TAM-Arkiv

TAGS: #raoulgalli #swedishitaliananthropologist #2015 #tradeunioncapital #pierrebourdieu #habitus #tradeunionbrandstrategy #togainrecognition #horisontalandverticalcompetition #tcoandsaco #interviewwithraoulgalli #interview #interviewbyleifjacobsson #niotillfem #workersofficialsandacademics